Ayame Tsutakawa and Family: A Cultural Journey through Dementia

Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage month is an annual celebration of diverse cultures, traditions, and migration histories, first designated by President Jimmy Carter in 1978. May was chosen to commemorate immigration of the first Japanese to the United States as well as completion of the transcontinental railroad. In addition, May is Older Americans Month—established by President John F. Kennedy in 1963 as a celebration of older Americans and a time to acknowledge their contributions to our communities.

According to the U.S. Census, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) are the fastest growing minority group in America. Between 2010 and 2030, the AAPI older adult population is projected to increase by 145 percent. As this aging population rapidly increases, AAPI older adults face a public health crisis similar to older adults from other ethnic backgrounds. Among many concerns, age is the largest risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease.

The National Resource Center on AAPI Aging, a program of the National Asian Pacific Center on Aging (NAPCA), celebrates Seattle’s AAPI older adult communities through an interview with Mayumi Tsutakawa, which follows. Mayumi Tsutakawa is an independent writer and editor who, together with her brothers and their wives, took care of her mother, Ayame Tsutakawa, for several years before she transitioned to the special unit for memory care patients at Keiro Northwest. Quotes are taken from an interview and essay Mayumi wrote in The International Examiner in September 2017.

Celebrating a Seattle Artist: Ayame Iwasa Tsutakawa

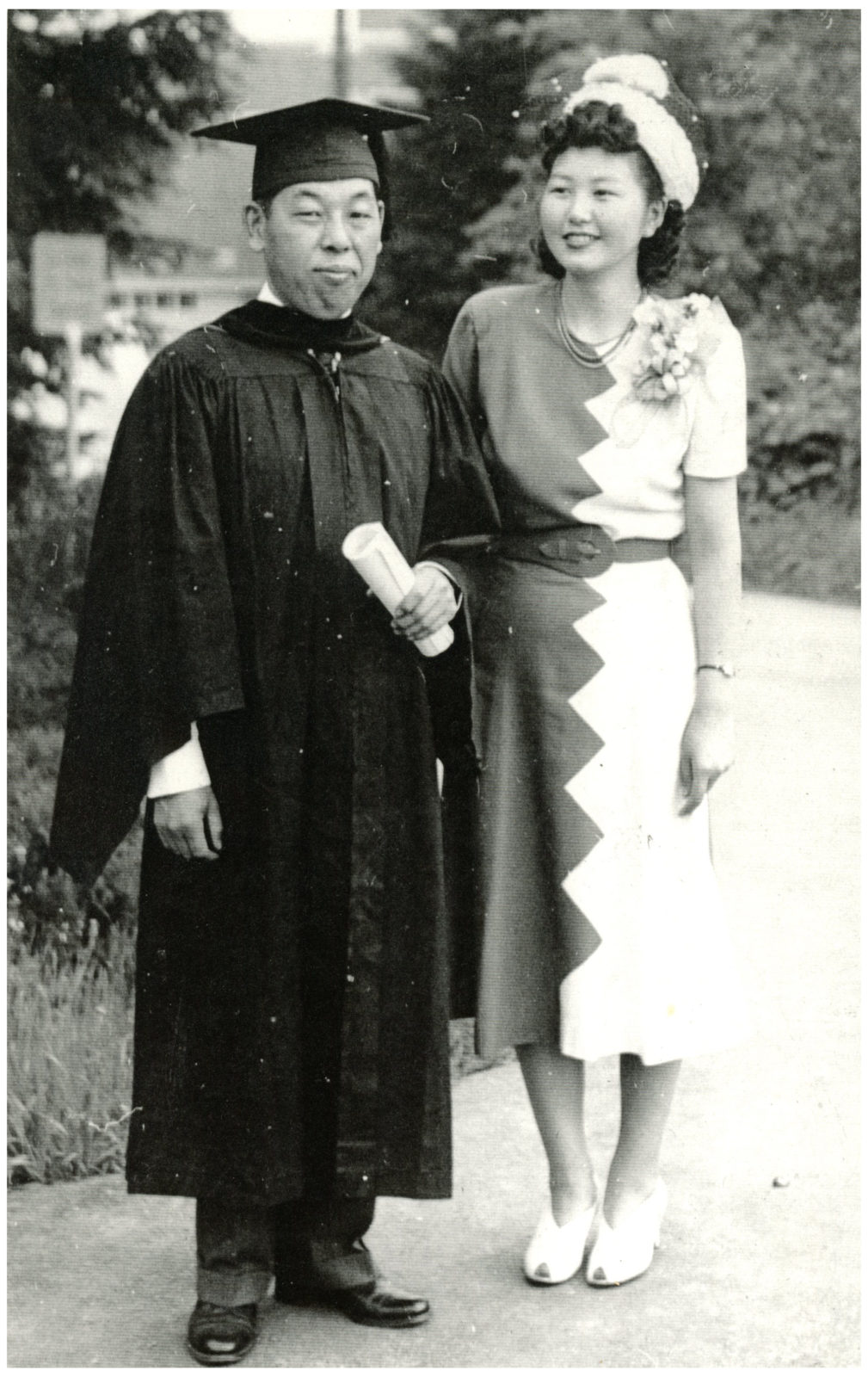

“Ayame was born in Hollywood, California, in 1924.” As Ayame’s mother “was a busy restauranteur, [she] was sent to live with relatives in Okayama, Japan, from the ages of 2 to 14. When she returned to the United States to live in Sacramento with her mother, she met a younger brother and a new stepfather. She became adept in Japanese traditional dance and music and was selected Miss Nisei Sacramento for the Golden Gate International Exposition in 1940. Like other Kibei Nisei who were born in the United States but raised in Japan, she was bilingual and continued a lifelong interest in Japanese arts and culture.”

Ayame’s “family was incarcerated at Tule Lake Camp in dusty northern California during World War II. The residents included many born or educated in Japan and Ayame performed traditional dance on stage there. In camp, she met Nisei artist and U.S. Army sergeant George Tsutakawa (1910 to 1997) who was visiting his relatives, the Moriguchi family. George also was Kibei Nisei, born in Seattle and raised in Okayama before returning to America … In 1947, Ayame moved to Seattle to marry George and she became an adept chef and hostess for events with local artists and those visiting from Japan.”

Mayumi Tsutakawa said, “For a decade and more, [Ayame] lived with dementia. Although she remembered less and had little logical thinking, she remained a gracious and polite Japanese lady who loved music of all kinds.”

AAPI Aging: When considering long-term care for your mom, what did your family look for from Seattle’s service providers?

Mayumi: “My brothers and their wives and myself all had taken care of my mother at home for several years. When it became 24/7 care and our favorite daytime caretaker left town, we were at a loss. We didn’t think she had bad dementia and should be placed in a memory care unit. But we checked with Seattle Keiro and were surprised to find out they had an opening. The staff gently convinced us to try the memory care unit. We were in denial about how much she needed that special care because she was physically fit. But Keiro was the only place we considered sending her because the bilingual Japanese service was important to us. As my Mom lost more memory and logic, she spoke more Japanese, the language of her youth. She did not realize which language she was speaking, English or Japanese.”

AAPI Aging: Do you have any advice for service providers who serve AAPI older adults with dementia?

Mayumi: “This depends on whether the resident is first generation and has limited/no English, or is second generation and mainly speaks English. The staff’s language ability is very important as the dementia patient becomes progressively more confused. If the staff does not speak Japanese, they need to hire some good interpreters or some very good bilingual volunteers. It would not be good for the staff to mistake a lack of English understanding for recalcitrance or unwillingness on the part of the patient.”

AAPI Aging: Do you see cultural stigmas preventing some AAPI families from seeking help for their loved one with dementia?

Mayumi: “Yes, this is true, but perhaps more so for the recently arrived/newer immigrants, who probably feel that they should care for their parent at home. Also, they might not have the funds to send their parent to a residential facility. The younger second/third generation children of parents with dementia might not be so hesitant to seek help, especially where the daughters and sons all work full time.”

AAPI Aging: How did your mom’s love of art evolve as her dementia progressed?

Mayumi: “My mother always loved art, it never diminished, although visual art was not as important eventually. She was trained in Japanese music in her younger years, and always loved music of all kinds—Japanese, Western classical, opera, and so on. She loved the music performances by musicians of all types that they provided at Keiro. She would nod and clap along with real accuracy. But as she exhibited more of the dementia, she really loved to recall the Japanese children’s songs of her youth. I brought recordings of these from Japan and we would sing along.

“The staff at Keiro were extremely patient and understanding. Even the non-Japanese staff learned many phrases in Japanese to help residents like our mother. [And] the staff played videos of Japanese music entertainment shows which [she] liked a lot! It didn’t matter how many times they were repeated.

“Ayame was dedicated to the idea that the growing and busy Asian American community here should learn about and appreciate the arts. She actively endeavored to get the non-Asian community to learn about Japanese culture. She organized one of the first Asian American art exhibitions at Wing Luke Asian Museum in the late ’70s. She became active in the Ikebana flower arrangement society, Asian Art Council of the Seattle Art Museum, and Kubota Garden.

“She leaves a legacy in the establishment of arts in Seattle. The wife of a noted Pacific Northwest artist, Ayame was invaluable in helping her husband to accomplish a life noted for his paintings, sculptures, and fountains. And she and George had four children, all involved in the visual and performing arts today: Gerard, Mayumi, Deems and Marcus. She also taught an appreciation for Japanese culture to six grandchildren.”

NAPCA thanks Mayumi for sharing Ayame’s legacy and the Tsutakawa family’s journey through her dementia progression. NAPCA would also like to acknowledge The International Examiner for its permission to use content from the article Mayumi authored in September 2017.

Ayame Tsutakawa passed away on August 16, 2017, at Keiro Northwest. She is predeceased by her husband, George Tsutakawa (1910–1997).

Learn what NAPCA’s National Resource Center on AAPI Aging—the nation’s first and only technical assistance resource center dedicated to building the capacity of long-term services and support systems to equitably serve AAPI older adults and their caregivers—is doing to develop culturally and linguistically accessible long-term services and supports for AAPI older adults with dementia (next article—or see link to “Developing Long-Term Services and Supports for AAPI Older Adults with Dementia” at right).

Contributor Heather Chun, MSW, directs technical assistance at the National Asian Pacific Center on Aging (NAPCA), based in Seattle. Learn more about NAPCA at www.napca.org.

This article originally appeared in the May 2018 issues of AgeWise King County (click here).

![Aging & Disability Services for Seattle & King County [logo]](https://www.agingkingcounty.org/wp-content/themes/sads/images/seattle-ads-logo.png)